What Should OPEC+ Do? What Would Russia Do?

In addition to Comments on Russia, The EU, China, Venezuela, Qatar, Germany, and the UAE

December 3, 2022

Main Takeaways

OPEC+ needs to flip the futures curve from contango to a steep backwardation by cutting production. Otherwise, oil prices will decline further in the coming weeks.

EU sanctions on Russian oil coupled with the G7/EU price cap will have a limited impact on Russia’s crude oil exports.

The mutual energy dependence between Russia & China will be useful for now, but dangerous for both countries in the long run.

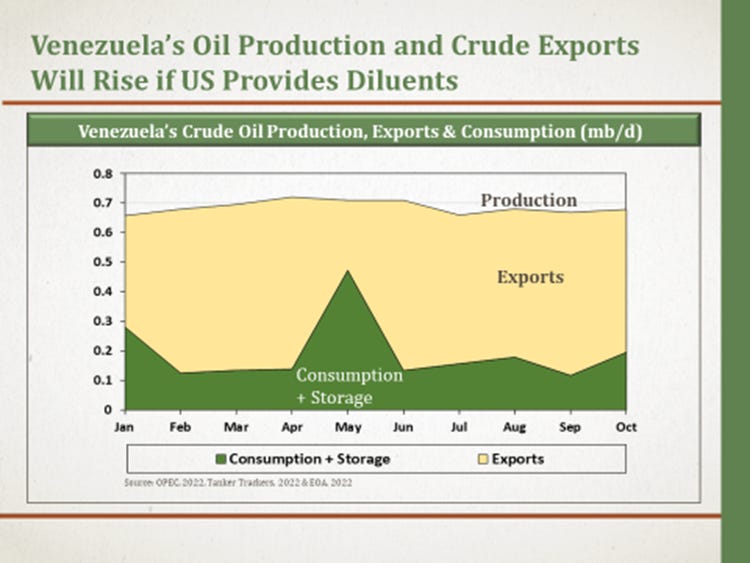

The recent US authorization for Chevron to “resume limited natural resource extraction operations in Venezuela”, and the subsequent agreement, has a marginal impact on the US and world markets unless Washington allows US shale companies to export diluents to Venezuela. In this case, Venezuela will be able to export an additional 300,000 barrels per day (b/d) to 400,000 b/d within a few weeks.

The Qatar-Germany long-term deal is a clear signal of the significance of energy security for the EU bloc. It indicates that gas will not be a fuel to facilitate energy transition but likely a destination fuel

FROM LAST WEEK’S HEADLINES

The oil market awaits the OPEC+ meeting on Sunday, December 4, with speculations that the group may maintain its current policy without additional cuts.

The G7/EU countries have reached an agreement at the eleventh hour to impose a $60/b price cap on Russian crude exports after days of bickering. But questions remain about the efficacy of such restrictions in curbing Moscow’s oil revenues.

Moscow and Beijing are closing ranks ahead of December 5 when a G7-proposed price cap and an EU embargo on Russian seaborne crude oil imports go into effect.

China’s protests over strict COVID curbs have led to speculations over whether Beijing may ease restrictions which could be translated into higher Chinese oil demand and probably higher oil prices. By Friday, December 2, the news was trickling in about restrictions being eased in some provinces and areas.

Washington has granted Chevron Corp a 6-month license to expand its oil operations in Venezuela, while still restricting direct payments to President Nicolas Maduro’s government. Venezuela signed contracts with Chevron on December 2.

TO THE POINT

It's been a week of speculations in the oil market. Ahead of the Group of Seven (G7) price cap on Russian oil, and European sanctions on Russian seaborne crude oil imports (piped crude oil excluded), which will take effect on Monday, December 5, the market has been guessing about the impact of these restrictions.

Although western governments have floated the embargo and price cap idea as effective ways to restrict Moscow’s oil revenues, the efficacy of these measures remains to be seen. Attempts to agree on a price limit have been mired in confusion amid divergent views from European countries over the level at which the price of Russian oil should be capped. And to top it off, the mechanism for implementing the cap remains questionable. Moscow has labeled this measure as “anti-market”, according to a report by Reuters, while stressing that Russian oil will not be supplied to countries supporting the price limit.

The uncertainty surrounding attempts by pro-Ukraine western powers to curb Moscow's oil revenues indicates that those restrictions on Russian oil will not be carved in stone and will be liable to change depending on how the implementation process goes, and how the EU consumer market reacts to the ban on Russian oil.

Another event that will be watched closely is the OPEC+ meeting on December 4 as there have also been speculations about the group’s next move ahead of the European ban on Russian oil. Similarly, developments in China have been monitored intently given that any decision to loosen Covid measures will imply higher demand for oil from the world’s largest energy consumer.

IN DETAIL

➢ OPEC+ Meeting

OPEC and its allies, including Russia (OPEC+), are expected to hold a virtual meeting on December 4 as the market awaits the group’s decision on oil output. Despite the prevailing speculation that OPEC+ may keep its policy unchanged, the group has options to make additional cuts or modifications to the existing cut to stabilize the market.

Last October, OPEC+ agreed to cut the production ceiling by 2 million b/d, a decision that will remain effective until December 2023. The effective cut is way lower and in the range of 800,000 b/d to 1.1 million b/d.

The group of oil producers is currently in a difficult situation amid volatile oil prices and will be required to strike a balancing act. Before looking at the various scenarios and their impact, it is essential to review the OPEC+ declared and undeclared objectives.

OPEC+ objective is to manage and balance the global oil market, reduce market volatility, and ensure that prices are high enough to stimulate upstream investment around the world. Experts in the oil market know—although this is not stated publicly by the energy ministers— that OPEC+ governments are after oil revenues, and therefore, oil prices.

Looking at oil prices, despite announcing the cut in October and acting on it in November, oil prices declined. The forward curve is in contango and oil prices might decline further, especially in December as investors reduce their exposure and traders shy away to reduce their risk and preserve their gains for the year.

Although gasoline prices in the US declined drastically in the last few weeks, a production cut by OPEC+ may not be welcomed by the US Administration. Therefore, what is the optimal action for OPEC+?

Before answering this question, it is worth pointing out that the Wall Street Journal’s report on November 21 that claimed Saudi Arabia discussed with other OPEC+ members an increase in production by 500,000 b/d has been officially denied by Saudi Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman. Additionally, claims that US President Joe Biden granted immunity to Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman in exchange for increasing oil production are a gross exaggeration. The Crown Prince was named in September as Saudi Arabia's prime minister, and under US law a prime minister has immunity in general. In a lawsuit in a US federal court, the Department of Justice (DOJ) had to file a document in the District Court for the District of Columbia stating that "the doctrine of head of state immunity is well established in customary international law." The DOJ has done this several times in the past with various foreign officials. Therefore, granting immunity to the Saudi Crown Prince is more of a routine and has nothing to do with raising oil output.

Back to the OPEC+, and to answer the question above, the optimal action that will achieve the above-mentioned OPEC+ objectives considering the current events and limitations in the oil market, is to move the forward curve for contango to a steep backwardation. This can be achieved in three ways:

OPEC+ moves the production cut from the fourth quarter (Q4) to the first quarter (Q1)

OPEC+ makes an additional cut in the first quarter or first half of the new year (2023)

Russian production drops because of sanctions and the price cap

Actions (2) and (3) are sub-optimal. The optimal action that will achieve all objectives at once is to move the cut from Q4 to Q1. This action would flip the curve to backwardation, stabilize the market, lower volatility, and increase prices and revenues. It will also assert the OPEC+ role in the market and convince investors that OPEC will not let prices decline. The idea that backwardation does not support investment is correct in the case of oversupplied markets with very weak prices, but this will not be the case in the coming years. If the cut in Q1 becomes too steep for some members, or a backlash from consuming countries is expected, OPEC+ can spread the Q4 cut on Q1 and Q2. The impact is less than moving the cut to Q1, but the situation will be better than the status quo.

The optimal action means no additional cuts during the meeting on December 4. The political ramifications of this decision would be less than those of the second and third actions. Making an additional cut will likely infuriate President Biden. The loss of Russian production is not optimal because the decline in Russian output might last longer than 2023.

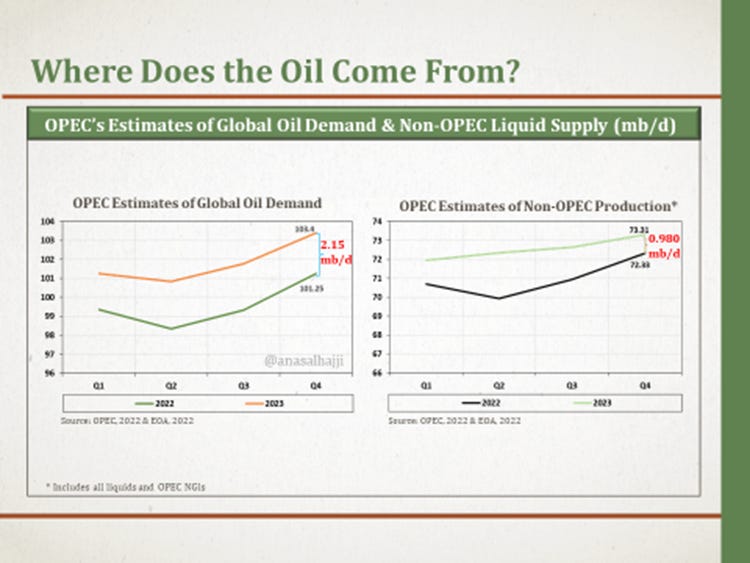

Here is why moving the cut from Q4 to Q1 is the optimal action: OPEC forecasts a major increase in world oil demand in Q4 2023, after remaining flat in the first quarter and declining in the second quarter as shown in the chart below on OPEC’s recent estimates of global oil demand in 2022 and 2023. The first problem with such estimates is that year-on-year (yoy), demand increases by a whopping 2.15 mb/d in the fourth quarter! But how will this increase in demand be met by that time?

OPEC estimates that non-OPEC liquid production in addition to OPEC Natural Gas Liquids (OPEC NGLs are not included in the quota. The quota focuses on crude only) will increase yoy by 980,000 b/d in the fourth quarter. Almost half of the growth in demand will be met by supplies from Non-OPEC and OPEC NGLs. Several experts and organizations do not agree with this assessment. They think it will be lower.

Here’s the problem: After the energy crisis in the US in the early 1970s that reached its peak with the oil embargo in October 1973, massive amounts of money were spent on oil market research, which attracted economists and political scientists from other fields. There was only one oil economist in the US at that time (Morris Adelman), but suddenly the US had many without any background in the oil business. Economists reached into their toolbox and started experimenting. For various economic and political reasons, they concluded that OPEC is a “cartel” or some sort of “monopoly”. Those early inexperienced researchers set the policy and literature tone for decades to come. Their impact is still felt today despite repeated modeling and policy failures. Why is this topic relevant to our discussion above? Bear with me.

The data above shows world oil demand and non-OPEC production (and OPEC NGLs which is not part of the quotas), but where is OPEC production? Welcome to the “Call on OPEC”! Since OPEC was assumed to be a “cartel” or a “monopoly”, it will always supply the difference between the global oil demand and non-OPEC production without studying its behavior or ability to do so!

That means world oil demand and non-OPEC production were estimated based on behavioral variables, but not OPEC production. The assumption that OPEC will always supply the difference caused crises in the past and will continue to cause crises in the future. To bring the idea home: Can OPEC deliver as global oil demand increases?

Based on the data in the above graphs, we can lay out the Call on OPEC as indicated below. What does the chart tell us?

First, while most oil bulls were fixated on the idea that OPEC+ members are not able to meet production ceiling or quota, they ignored the fact that OPEC's actual production in the third quarter was way higher than OPEC’s estimates of the “Call on OPEC.” In other words, while oil bulls thought not meeting the quota was bullish, actual production was bearish, especially in the fourth quarter since it takes 6-12 weeks for the oil to reach its destinations. Of course, there were multiple reasons for the price decline in Q4 including Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) releases, but it is flat wrong to assume that producing under quota is bullish. The ceiling was an imaginary target used for accounting purposes. You cannot be bullish on imaginary targets.

Second, look at the “Call on OPEC” chart, then look at the chart of non-OPEC production above it: Can they deliver? If non-OPEC cannot deliver, can OPEC compensate?

Third, remember that the OPEC cut covers all of 2023. That means the cut covers Q4 2023! If they maintain the cut, the 1 mb/d of growth in the call on OPEC will not be there! How will the estimated demand be met then?

It will be difficult to cut production in Q4, 2023, because of strong demand. The market is weak now and will remain so in Q1. However, if the cut was moved from Q4 to Q1, OPEC+ will achieve all its stated objectives and will not need to cut in Q4. Demand will be too high.

Unfortunately, the probability of OPEC+ adopting this policy is low. Based on current news and insights, the likelihood of maintaining the status quo is high. In this case, oil prices are expected to decline, probably to as much as $10/b. Regardless, never underestimate OPEC+'s ability to pull a rabbit out of the hat.

➢ EU Ban and G7 Price Cap

“The potential unraveling of the old order in the global oil market will reach a defining moment over the next week,” wrote the Financial Times in an article published on November 28 ahead of western restrictions on Russian oil starting December 5.

It remains to be seen how the G7 price cap combined with the European ban on Russian seaborne crude oil imports will surely create new trends in the oil market (cap on oil products will start on February 5). Although the chief of the International Energy Agency (IEA), Fatih Birol, expected in an interview with Reuters in late November Russian crude production to be curtailed by around 2 million b/d by the end of the first quarter of next year, it is too early to predict the drop in Russian output.

The situation echoes the events of 2018 when the US re-imposed sanctions on Iran’s oil industry. At that time too, the oil market was brimming with speculations over Iranian oil exports which since then have never stopped flowing. In the same way, US sanctions on Iran, as well as on Venezuela, carved new directions in the oil market with both countries resorting to various schemes to keep selling their oil despite restrictions, Russia is expected to follow suit, and this has already started to happen.

Russian oil imports made up 25% of total EU oil imports last year, according to the BP Statistical Review of World Energy. These trades, however, are bound to change as Moscow diverts its oil supplies from Europe to countries in Asia, mainly India and China, in addition to Turkey and Egypt, among others.

China and India’s imports of Russian crude oil (mostly ESPO and Urals) have been soaring so far this year compared to the last 3 years. Figures from data intelligence firm Kpler show that while India imported around 56 million barrels of Russian crude in 2021 (full year), so far this year (Jan-Nov), imports have reached around 307 million barrels. China, meanwhile, has imported some 414 million barrels so far this year, while imports of Russian crude were at around 316 million barrels in 2021 (full year).

Our view is that the impact of sanctions and the price cap on oil markets is limited. Russia was able to increase its exports in recent months as shown in the chart below, despite warnings of a major decline in Russia’s crude exports. The chart shows Russia’s seaborne crude exports.

Russia was able to shift a large amount of crude from European markets to Asian & Middle Eastern destinations as shown in the two pie charts below. The charts compare Russian seaborne crude exports between November 2021 and November 2022.

The November 2022 chart shows that about 1.6 m b/d went to Europe in November. A static view of the market indicates that sanctions starting early next week would force Russian oil companies to cut exports by the same amount. But a dynamic view, coupled with several facts, indicates that:

1- Some European countries wanted to “fill up” before the sanctions and Russia was happy to supply them. That means the actual amount that would have gone to Europe if sanctions were delayed or not implemented will be smaller.

2- Some of the 1.6 mb/d that was shipped to Europe in November will be diverted to other countries as exports or part of swap deals.

3- Some Russian oil will still end up in Europe following the oil embargo under different names using various shipping schemes that Iran has been using for years.

Our estimate is that Russia may not be able to find a market for about 300,000 b/d-400,000 b/d. Will that end up in floating storage? In ghost ships? Or will it be refined and exported, since refined products are not included in the sanctions that will go into effect on December 5? Or will that lead to a production shutdown? Whatever the case, it will have some impact, unless this same amount was covered by Venezuelan crude exports as discussed below.

It is also worth noting that some OPEC+ members who are convinced that their oil in the ground will be worth more in the future, can cut their own production and import cheap Russian oil to run power and desalination plants. Once world oil demand and prices increase, OPEC+ members can also continue importing cheap Russian oil and export their own crude at higher prices at the same time. In the case of weaker demand, some OPEC members may cut their oil production, but Russian output will not be affected. So regardless of the circumstances, they will all benefit.

As for the price cap, the $60/b limit which was agreed on December 2, is higher than the current price of Russian Ural by several dollars. The price cap is effective only if it is implemented by force of arms, and only if it is lower than the market price. Since the price cap is higher than the market price by several dollars, and there will be no enforcement even if it were lower than the market price, we believe the price cap will not have an impact.

➢ China and Russia Bolster Ties

A few days before the EU imposes its ban on Russian seaborne crude oil imports, and the price cap goes into effect, Russia and China have been displaying unity, particularly over energy matters.

"China is willing to work with Russia to forge a closer energy partnership, promote clean and green energy development and jointly maintain international energy security and the stability of industry supply chains," Reuters quoted Chinese President Xi Jinping as saying during the Fourth China-Russia energy forum in late November.

The CEO of Rosneft Igor Sechin, meanwhile, said at the forum that Russian energy companies were ready to “submit proposals to their Chinese partners in all key areas of cooperation in the fuel and energy complex," Russian TASS news agency reported.

Last month, Russia’s Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak said that his country’s energy exports to China have increased in value “by 64% this year, and by 10% in volume”, according to Reuters.

However, China imports oil from Russia by sea and via pipelines. Novak’s comment referred to seaborne shipments only (see chart below). Pipeline imports were flat yoy, probably because of pipeline capacity. China imported about 775,000 b/d via pipeline in the first ten months of this year.

One could argue that China is being opportunistic and chasing low oil prices. But its mega infrastructure deals and long-term supply commitments of oil and natural gas indicate otherwise. While increased energy dependence is useful for both countries, for now, it may backfire in the long run. China’s energy security requires more diversification, while Russia’s dependence on the Chinese economy increases the economic and political risks for Moscow.

➢ Chevron and Venezuela’s Crude

In late November, Washington granted Chevron Corp a six-month license to expand its energy operations in Venezuela, a decision that was interpreted as a change in the US policy towards Caracas. This move, however, is unlikely to have a substantial impact on the global oil market. Venezuelan crude oil exports since September have been less than 600,000 barrels per day, according to TankerTrackers.com which tracks physical exports out of the country using AIS signal and satellite imageries.

Although the US has given Chevron the green light to resume oil production in Venezuela, the Venezuelan government will not be able to benefit from oil sales due to US restrictions on direct payments to the Maduro government. According to a report by the Financial Times, “revenues will be used to repay the debt to Chevron.”

While demanding that US sanctions be lifted, Venezuela signed on December 2 contracts with Chevron to continue working on the joint ventures between state-run PDVSA and Chevron: Petroboscan and Petropiar.

According to Reuters, Chevron is seeking to start receiving shipments of Venezuelan oil as early as this month (December) and which will be required to flow to US refiners who use this type of crude.

We believe the impact of such a deal is limited. The amount to be added from joint ventures is about 200,000 b/d and will take time to be achieved. We also believe that the Biden Administration’s initiative to grant Chevron a six-month license was related to issues with crude quality, not quantity. Due to continuous withdrawals, most of the heavier sour crude oil has been drained from the SPR, and Venezuela is one of the main sources of this type of crude.

It makes perfect sense now for Washington to extend licenses beyond Chevron operations in Venezuela. Allowing US shale producers to export diluents to Venezuela is critical for increasing production in Venezuela. In this case, Venezuela’s oil production and exports would increase by 300,000 b/d to 400,000 b/d in a few weeks.

➢ Germany-Qatar LNG Deal: Implications for Qatar and Europe

In late November, Qatar’s state-run energy company QatarEnergy signed two LNG long-term contracts with the US energy firm ConocoPhillips to supply Germany with Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG). According to the agreement, Qatar will supply about 2 million tons per annum (2 MTPA) of the super-chilled fuel to Germany for a 15-year period, with the first shipment starting in 2026. This means gas will remain a key component in Germany’s energy mix until 2041.

North Gas Field Expansion

Under this historic deal, the LNG shipments will be sourced from two joint ventures between QatarEnergy and ConocoPhillips, the North Field East (NFE) and North Field South (NFS) projects. These two will roughly add 33 MTPA and 16 MTPA respectively to the existing LNG capacity, which will enable the gulf state to increase its LNG capacity from 77 to 126 MTPA by 2027.

For its part, ConocoPhillips would purchase the agreed volume to be delivered Ex Ship (i.e. shipped and delivered at the terminal) to the Brunsbuettel LNG receiving terminal which is currently under construction in northern Germany.

This deal comes one week after another significant deal QatarEnergy had secured with China’s energy giant Sinopec, under which Qatar will supply the Chinese firm with 4 MTPA starting in 2026 and for a 27-year period. This is the largest single LNG sales and purchase agreement (SPA) in the LNG industry!

Qatar has always preferred long-term contracts in its LNG business because it guarantees continuous revenues, and secures the required cash flow to continue pouring investments into its natural gas resources.

A Breakthrough in the EU but the Start of a Tough Journey

For Qatar, the deal with Germany can be considered a breakthrough in the largest economy in the EU bloc and its largest gas market. Moreover, this is the first long-term LNG deal to be signed between a European country and LNG sellers. But this is the beginning of a tough journey for Qatar. So far, the Gulf state has only secured the sale of 6 MTPA or 12% of the North Field Expansion projects and needs to continue hard talks and negotiations with other potential European and Asian customers to secure the sale of remaining uncontracted volumes as shown in the chart below, which shows the capacity and timeline of North Gas Field expansion SPAs deals.

Energy Security: A Top Priority for Europe

Europe has always preferred not to sign long-term contracts with any seller to facilitate getting rid of fossil fuels and encourage investments in renewable energy resources. Such policy, however, was not sufficient to ensure energy security for Europe and avoid exposure to highly volatile spot gas prices which are currently trading at historic highs in comparison with term gas prices.

Historically, Germany has never imported LNG because it lacked the required infrastructure, and was dependent on Russian gas flows via Nord Stream 1 pipeline and the transit pipeline networks—passing through Ukrainian territories— to meet more than half of its gas needs. Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Germany decided to move away from piped Russian gas and halt any remaining flows from Russia by the summer of 2024.

To that end, Germany has taken concrete steps to ramp up LNG imports, securing up to six Floating Storage and Regasification Units (FSRUs), spread over four sites, with a total annual capacity of more than 30 billion cubic meters (bcm), as shown in table (1). The six FSRUs are expected to be fully operational by the end of 2023. Collectively, they could cover up to one-third of Germany’s annual gas demand (95 bcm in 2021) and effectively help the European country move away from Russian piped gas.

The Qatar-Germany long-term deal is a clear signal of the significance of energy security for the EU bloc. It indicates that gas will not be a fuel to facilitate energy transition but likely a destination fuel. The deal will keep natural gas a key component in Germany’s energy mix till 2040, and probably beyond. Furthermore, it is the first collaborative action by the EU to wean itself off Russian gas in the long run and replace it with long-term LNG shipments from giant gas producers like Qatar.

➢ United Arab Emirates National Day

Some people may forget that the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is a federation of seven states, with each state having its rulers and own laws and regulations.

On December 2, 1971, the rulers of six sheikhdoms, Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Ajman, Al-Ain, Sharjah, and Umm al-Quwain, agreed to form a union and announced their independence from Britain. They decided to name their country the United Arab Emirates. They were later joined by Ras Al Khaimah.

Oil was discovered in 1958 near Abu Dhabi, which joined OPEC in 1967. After the union formation, Abu Dhabi’s membership was transferred to the UAE. According to various sources, including OPEC, the UAE’s population is about 10 million with a per capita income of around $66,000 (PPP dollars).

While the UAE is a leader in renewable energy, it has the sixth largest oil reserves in the world with 107 billion barrels, according to the Oil and Gas Journal. In November, it produced 3.186 mb/d according to OPEC’s monthly report. ADNOC announced plans to invest $150 bn over the next five years. ADNOC’s objective is to increase its oil production capacity to 5 mb/d by 2030.

The United Arab Emirates’ role in the global oil market is expected to increase in the coming years as the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) plans to boost investment over the next five years. Meanwhile, it remains to be seen if the UAE will exit OPEC+ in the coming years as it increases its oil production capacity. Yesterday, December 2, was the UAE National Day.

Below are a few charts showing the UAE’s oil reserves, oil production, and oil consumption.

Those who are interested in charts on the UAE’s natural gas, please let us know and we will send them your way!