Understanding Pricing Mechanisms in International Gas Trade

and an Update on Oil Market Outlook

In this issue:

1- Understanding Pricing Mechanisms in International Gas Trade

2- Oil Market Outlook: An Update

Understanding Pricing Mechanisms in International Gas Trade

Several mechanisms are used to determine the level at which gas is priced and sold in different regions. Generally, there is no single global reference, and gas prices have to be set locally or regionally.

Historically, long-term and take-or-pay sale and purchase agreements (SPAs) between producers and consumers were the only way to determine the price of gas exports. These agreements were indexed to crude oil or oil products to guarantee the supplier a sufficient return on investment in the capital-intensive gas value chain. With the introduction of the LNG trade, the number of producers and consumers started to increase, and new price formations and contracting schemes emerged. In gas markets, gas price formation mechanisms can be divided into two main groups: regulated gas pricing and market-based pricing (see Figure 1 below).

Group-1: Regulated Gas Pricing

For the regulated gas pricing group, there is no market approach, but rather the regulatory body (governments) has the authority to set natural gas prices at the level required to meet its domestic energy policies or social objectives. This price mechanism is used mostly in domestic markets. In the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, for instance, governments could set the price at a certain level for some large consumers, like the petrochemical sector, to ensure the cost-competitiveness of its products for export purposes. The gas price could be also set at a fixed value for the power generation sector to support the social well-being of the population.

In interregional gas trade, the regulated pricing scheme could be applied in bilateral agreements that are usually concluded at the government or state-owned company level. In this type of agreement, there would be a single dominant buyer or seller, or at least one side of the transaction, while the price is fixed for a specific period of time. The contracts signed between Russia’s gas giant Gazprom and China’s state-owned company CNPC are examples of bilateral agreements based on a regulated pricing scheme

Group-2: Market-Based Gas Pricing

In a market-based pricing environment, the price of a commodity is determined by the dynamics of supply and demand. That said, increases in natural gas supply will generally result in lower natural gas prices, while decreases in supply will put upward pressure on prices. However, gas prices may be linked to other products like crude oil or oil products instead of the interplay of supply and demand of natural gas.

There are two types of market-based pricing: gas-on-gas competition (GOG) which is mainly applied in gas trading hubs, and oil price escalation (OPE). We discuss the two below.

Gas-on-Gas (GOG) Competition

The gas-on-gas (GOG) competition is the most used market-based pricing in international trade. According to the International Gas Union, the gas price in the GOG category is determined by the interplay of supply and demand, and gas is traded over a variety of different periods (daily, monthly, annually, or other periods). Trading can take place at physical hubs (like Henry Hub (HH) in the US) or notional hubs (like the National Balancing Point (NBP) in the UK). This category also includes spot LNG cargoes that are usually delivered between 4 to 12 weeks after the transaction date, in addition to any pricing linked to the hub or spot prices. Moreover, the category includes bilateral agreements in markets where there are multiple buyers and sellers, to distinguish them from bilateral monopolies.

Markets that are based on the GOG mechanism are the most liberal and liquid ones, characterized by large numbers of buyers and sellers mostly competing without government intervention. These markets have ample pipelines and gas storage systems with the possibility to either export or import gas. Any volume of gas can be traded on both current and future contracts. This will enable the efficient use of gas infrastructure and allow both buyers and sellers to plan for their financial future. The GOG mechanism is applied in the US and Europe, using well-established benchmark price indices (HH in the US, NBP in the UK, and Title Transfer Facility (TTF) in the Netherlands) as shown in Figure (2) below.

Turning to spot LNG trade, there are several benchmark indices, including the Japan-Korea Marker (JKM), which is the price assessment for spot physical LNG cargoes delivered ex-ship (DES) into Japan, Korea, China, and Taiwan, between 4-12 weeks from the transaction date.

Oil Price Escalation or Indexation (OPE)

Under this mechanism, the gas price is linked, usually with a floor price and escalation clause, to competing fuels; typically crude oil (Brent). This pricing mechanism is originally used in traditional LNG markets in Northeast Asia, particularly Japan, to ensure that imported LNG is traded at a discount to imported crude oil.

The OPE is most often used for international trade, especially in term contracts that could last for 10-15 years. In many current contracts, one MMBtu (Million British thermal units) of LNG can be priced at 12-15% of Brent oil barrel. In full oil parity (100% indexed to oil), the price of one MMBtu of oil-linked LNG is equivalent to (17.2%) of a barrel of crude since one oil barrel has an average energy content of 5.8 MMBtu.

Another gas pricing formation mechanism could apply a complex formula that includes the prices of substitute fuels, such as crude oil or oil products, as well as gas market price indices (such as HH or TTF). This is called hybrid pricing which emerged in Europe and is used along with spot gas traded at hubs, and oil-indexed gas.

Units of Gas Used in Pricing

Unlike oil which is sold per unit of volume or mass, gas is sold per unit of energy. Gas could be sold in US dollars per million British thermal units ($/mmbtu) or US dollars per megawatt hour ($/MWh). In Europe, gas is traded at TTF in euros/MWH while in the US it is traded at HH in $/mmbtu.

Pricing Structure of Gas and LNG Trade

The total natural gas and LNG trade is split between three categories (GOG, OPE, and BIM). In 2021, the International Gas Union estimated that GOG accounted for 56% of total trade, while OPE accounted for 39%, and the remaining 5% was the share of BIM (see Figure 3 below).

The Spread between Gas Prices in Different Regions

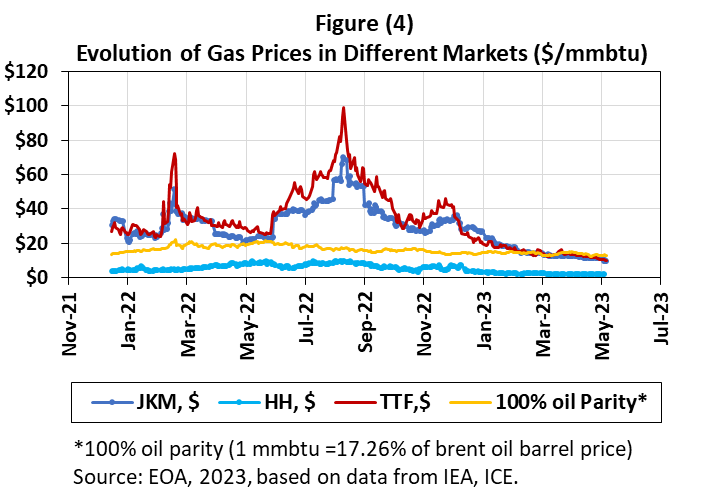

Different prevailing gas pricing mechanisms result in large variations in price levels across the world. That said, gas prices in the US are always lower than those elsewhere. In Asia, gas prices are usually higher than Europe’s, but recently the spread between TTF and JKM has diminished on the back of the gas crisis in Europe amid dwindling Russian gas supplies (see Figure 4 below). In oil-indexed term contracts (for instance 100% oil parity), the LNG prices are characterized by their stability and are less vulnerable to supply changes than hub prices— thanks to the stability of the oil market. Gas volumes traded at hubs are the most volatile since they are vulnerable to the supply-demand balance, and are also affected by seasonality, changes in gas inventory levels, and geopolitical developments affecting gas supplies.

As the international gas trade continues to expand to meet growing energy needs, understanding how natural gas and LNG prices are determined becomes crucial for all market players, including producers, consumers, investors, and traders, among others.

2023 Oil Market Outlook: An Update

Earlier this month, the International Energy Agency (IEA), OPEC, and the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) released their updated views on the oil market which we summarize below.

Global Oil Demand Growth

Figure (1) below shows the most recent estimates of global oil demand growth by the IEA, OPEC, and the EIA. The three revised up their estimates and all are bullish. Our concern is that data on China’s oil market is still questionable since the giant Asian oil importer may be refilling its strategic petroleum reserve.

Growth in Non-OPEC Production

Figure (2) below shows growth in non-OPEC production in 2023 as estimated by the three organizations in their most recent monthly reports. These forecasts are also bullish since there was a slight decrease.

All forecasts, including ours, are bullish on oil in the second half of 2023. While most organizations and analysts agree on this point in the absence of a recession, they disagree on the magnitude; in other words, on the levels of inventory withdrawals, and on the rise in oil prices. And that’s why all eyes now are on the upcoming OPEC+ meeting.

OPEC+ Meeting: EOA’s Main Takeaway

OPEC+ is expected to meet on June 4. Any statements issued from now and until this event by politicians in the US, Europe, Russia, or by OPEC+ members and the IEA are most likely linked to the meeting which the market will be watching closely.

Here’s what we know: OPEC is bullish on oil demand and sees global inventories declining. The group also sees the decline in oil prices in recent weeks as a result of an extreme bearish sentiment by speculators, and financial problems stemming from the banking crisis. OPEC’s view, regardless of whether it is right or wrong, is that its decision to implement voluntary output cuts has been a precautionary measure to influence the sentiment.

However, we see a conflict between the idea of implementing voluntary cuts and extending them until the end of 2023 on the one hand and OPEC’s bullishness on the other. If OPEC’s forecasts are correct, we believe the group will end up increasing production this year.

Going back to the upcoming OPEC+ meeting, so far, we believe that it will flow smoothly without fireworks, but this could change in a New York minute.

An average Brent price of $75 for the rest of the year is considered favorable to all OPEC+ members. The problem is that given the sentiment among some traders, they consider the act of maintaining the status quo as bearish. What could change this sentiment are impactful actions such as making OPEC’s voluntary output cuts official, and announcing additional voluntary cuts by Saudi Arabia and its allies. For example, Saudi Arabia and its Gulf allies could announce an additional 1 mb/d cut for the months of July and August. Another action on the part of OPEC would be convincing Russia to lower its oil exports.

We will share more details with our readers in our mid-year updated outlook which will be published in June.