Rumor Mills of another Oil Price War? No, it’s far simpler than that.

What are the conditions to launch an oil price war? (With 12 charts)

The oil market is not competitive. It is a mix of oligopoly (small group of producers) and oligopsony (few large influential consumers) with government interference through heavy regulations, taxation, and subsidies (mostly targeting consumers).

It is known in the literature that oligopolists can punish competitors or those who do not conform to the rules, by increasing production and lowering prices until they either push them out of the market or force them to comply. Oligopolists usually resort to this strategy when all other options fail. Saudi Arabia did this in the mid-1980s, 2015-2016, and in 2020 (Some experts believe that we should add the 1998-1999 period. They say the Saudis increased production to punish Venezuela which increased production and refused to cut). The threat of doing so has always been there, and it can be eliminated neither now nor in the future. Some would argue that this behavior amounts to weaponizing oil. The literature is clear that the act of using oil as a weapon is intended to achieve POLITICAL goals. But the objective of an oligopolist is financial, not political. So, in short, any price war to force production compliance is not classified as an “oil weapon”.

While the threat of flooding the market and starting a price war is there, we discount this possibility, at least for now, for the reasons listed below:

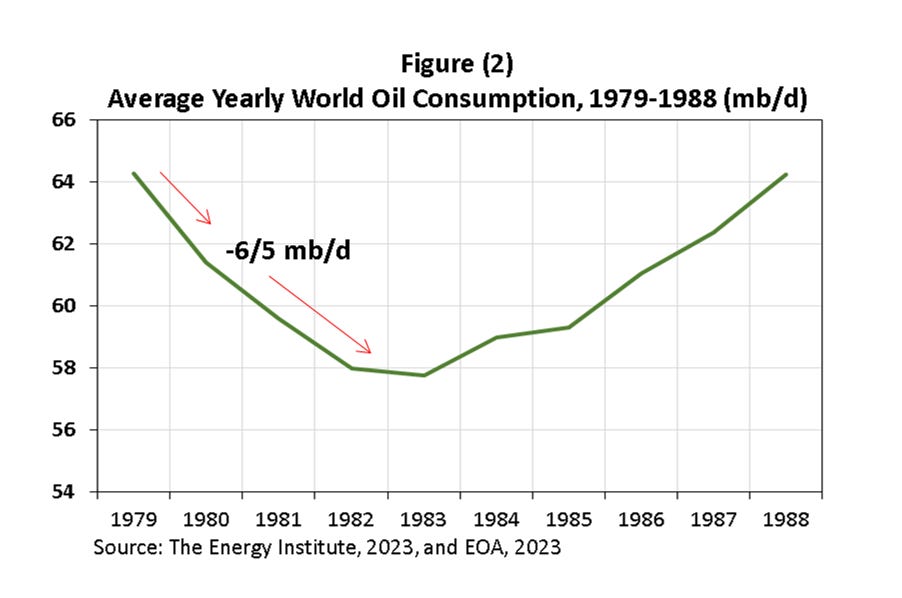

1- In the mid-1980s, Saudi Arabia cut production by 80%. Yes, 80% - this is not a typo. Although they cut production from 10 mb/d to 2 mb/d in certain months, prices continued to decline, despite the war between Iraq and Iran during that period (see Figure 1). Several OPEC members refused to cooperate on reducing output, and instead, they increased production, mainly Nigeria. At that time, production from the North Sea and Alaska increased by more than 5 mb/d! Oil prices were below marginal cost. But that’s not the case now. Saudi production today is at 9 mb/d. Additionally, demand is expected to grow, and non-OPEC production growth is not as large as it was in that period. In the 1980s, massive production additions came online, especially from Alaska and the North Sea with gross production above 5 mb/d, while demand tanked by about 5 mb/d! Again, demand now is growing.

The figures below sum up the situation in the mid-1980s. Production in the North Sea and Alaska soared as shown in Figure (1). It is not only the increase in oil production that mattered but also the location: both are near OPEC’s traditional markets in the US and Europe. World oil consumption declined as shown in Figure (2). Consumption declined because of high oil prices in the 1970s and early 1980s and the various measures taken to reduce oil consumption. As a result, Saudi Arabia cut production as shown in Figure (3). The data is yearly but monthly figures show way lower production in certain months. As prices continued to decline and some OPEC members refused to cooperate and cut production, Saudi Arabia increased production and prices declined as shown in Figure (4).

2- In 2015-2016, there were major oil additions from shale, Russia, and several OPEC members, including Iraq, as demand significantly slowed down due to high oil prices, and other macroeconomic issues. Between 2010 and 2013, the average growth in oil consumption was about 1.57 mb/d, but it sharply declined to about 700,000 b/d in 2014, around 1 mb/d lower than earlier expectations. Going back to production, global outputs massively increased by 5.1 mb/d in 2014 and 2015, of which 3.56 mb/d came from producers outside OPEC. That’s not the case now.

Figures 5-8 sum up the story of the oil market in 2015-2016. Oil production in Canada, the US, Russia Iran, Iraq, and the UAE increased significantly as shown in Figure (5). Demand slowed down in 2014 as shown in Figure (6). Saudi Arabia increased its production as shown in Figure (7), and prices plummeted as shown in Figure (8).

3- In March 2020, and to use a terminology introduced by Saudi Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz Bin Salman, the oil market was on fire, and this required an immediate response. Russia wanted to bring the garden hose instead of calling the fire department. But Saudi Arabia knew using the garden hose wasn’t the right reaction and decided to call the Fire Department to protect the market by forcing Russia to cut production. His statement regarding “garden hose” vs. “calling the Fire Department” explains the differences in views between Saudi Arabia and Russia.

When Russia refused to cooperate, the Saudis retaliated by lowering Aramco’s OSPs significantly and increasing supplies to nearly 12 mb/d. Prices collapsed. That’s not the case now.

President Trump interfered and asked all parties to cut production. The result was a total cut of 9.7 mb/d that was announced in April 2020.

In both instances, in the mid-1980s and in 2015-2016, a price war erupted because of large increases in production and a decrease in demand or a major slowdown. In March 2020, it was all about a major decline in demand because of COVID-19 and its aftermath. The story is summed up in Figures (9) to (11). Saudis foresaw the decline in demand that Russians did not. Saudi Arabia increased production as shown in Figure (10). Prices plummeted as shown in Figure (11).

No Oil Price War

The above discussion leads to one clear conclusion: Saudi Arabia resorts to a price war when it sees a massive surplus in the market that others do not see or see but choose to ignore. In past instances, the surplus exceeded 5 mb/d! In past price wars, the increase in production outside Saudi Arabia was large while the decline in demand was also large. This is not the case today. Demand is growing but at a lower rate than earlier expectations. The increase in production in non-OPEC is still manageable.

There have been claims that Saudi Arabia and other OPEC members are worried about non-OPEC production (hence the rumors of price war). This is inaccurate. OPEC has been predicting such increases since the end of 2022. Figure (12) below is extracted from OPEC’s Monthly Oil Report published in December 2022.

In short, non-OPEC production did not surprise OPEC. The surprise was demand growth being lower than forecasts and the Chinese releases of inventories to prevent oil prices from rising.

Conclusions

Evidence from previous price wars shows that Saudi Arabia resorts to a price war when the existing or the foreseeable surplus in the oil market is massive and more than 5 mb/d and other OPEC/OPEC+ members do not see it or ignore it. This massive surplus is usually the result of a large increase in production, mostly from non-OPEC members, and a large decrease in demand. In the case of March 2020, there was a major decline in demand. This is not the case now. World oil demand is still growing, although at a lower rate than earlier expectations. For 2024, OPEC expects global oil demand to increase by 2.2 mb/d, the EIA by 1.4 mb/d, and the IEA by 0.930 mb/d.

The increase in non-OPEC production remains manageable. For 2024, OPEC expects non-OPEC production to increase by 1.38 mb/d, EIA by 1.2 mb/d, and the EIA by 1.14 mb/d.

The current differences among OPEC+ members can be easily resolved, and the most likely scenario for OPEC+ + meeting on November 30 is an agreement— if not among OPEC+ members, then between Saudi Arabia and its allies within OPEC+. We will discuss these issues in detail in the next report that we will post tomorrow. EOA