Iraq’s Energy Sector: Twenty Years after the US Invasion

Can Iraq increase its oil production capacity from 5 mb/d to 8 mb/d?

Four days after the 20th anniversary of the US invasion of Iraq, an international court of arbitration sided with the federal government of Iraq against Turkey for allowing crude oil to be exported by the semi-autonomous Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) via the Turkish port of Ceyhan without Baghdad’s permission, and in violation of a 1973 pipeline agreement. This is one of the many legacies of the 2003 invasion.

The court ruling implies that Erbil can no longer export its crude oil independently. The flow of around 450,000 barrels per day (b/d) from the northern Kurdish region and the Kirkuk oilfields to Ceyhan came to a halt following the court decision. The official announcement came as Erbil and Baghdad have been holding talks to address divisive issues related to oil output and exports, as well as the KRG’s share of the federal budget. Last year, tensions erupted between the two after the Iraqi Federal Supreme Court ruled that the KRG’s 2007 oil and gas law was unconstitutional. The court also demanded that the KRG hand over crude oil production to the central authorities. Baghdad has maintained the view that the Kurdistan region is not entitled to run the oil sector independently of the federal government or sign contracts with foreign oil companies. But the legal interpretations surrounding this issue vary.

Although 450,000 b/d exported via Turkey’s Ceyhan port have been suspended since Saturday, it is our view that exports will resume soon, although talks that have taken place between Erbil and Baghdad in the past few days have not been productive, according to a Bloomberg report published today.

Our view is that the impact of Iraq’s latest developments on global oil markets is limited. We believe that crude oil exports will resume soon because both Baghdad and Erbil export their crude via Ceyhan. The federal government exports around 75,000 b/d of crude via Turkey, according to Reuters. We also believe that an agreement will be reached quickly since all parties are losing from the halt of crude exports via Ceyhan.

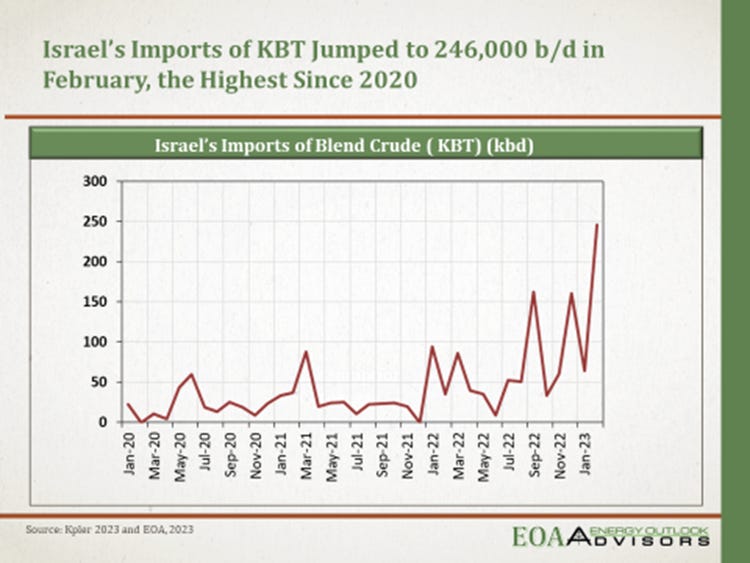

With respect to the Kurdistan blend crude (known as the KBT) which is exported by the KRG, most exports have been flowing to Israel recently amid a decline in exports to Europe. Israel increased its imports of KBT via the Ceyhan port in February, as shown in Figure (1). We suspect that Israel can manage the temporary halt in KBT flows by drawing on inventories or importing more crude from Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan (BTC Azeri and CPC blend).

Figure (1)

We wanted to share our main takeaway on the unfolding developments between Baghdad and Erbil before taking a deep dive into Iraq’s energy sector 20 years after the devastating US invasion.

Although federal Iraq today is trying to address some deep-rooted problems in its energy sector and accentuate its sovereignty over all oil operations, it is unlikely to succeed in modernizing its energy sector without vital reforms. Twenty years after the US invasion, Iraq remains heavily reliant on oil revenues which make up around 90 percent of its budget. Focusing on oil production and crude oil sales without developing in parallel other vital sectors and undergoing the necessary institutional and economic reforms, will not encourage economic and energy development in OPEC’s second-biggest producer.

The 2003 Invasion: Overview

The US invasion of Iraq in 2003 shattered a country that was already suffering from dictatorship and devastating international sanctions that crippled vital infrastructure. The long-lasting impact of the destructive war launched against Iraq 20 years ago is felt in the energy sector which we will be discussing in detail in the following sections.

In the oil sector specifically, Iraq’s oil production has faced a plethora of challenges following 2003, but oil kept flowing. Although output came to a halt after the invasion on March 20, 2003, the pumping of crude resumed in a few weeks. Production was around 2.5 mb/d in 2003, and towards the end of 2015, it stood at about 4.4 mb/d (from southern and northern oilfields). This was the result of the contracts which Iraq signed with International Oil Companies (IOCs) in 2009 and 2010 to develop its oilfields, as part of the bid rounds, and when oil prices were high. But they turned into a burden during the low oil prices environment since they are based on a fixed-fee service. According to Gary Volger, author of Iraq and the Politics of Oil: An Insider’s Perspective, “the contracts were negotiated when prices were around $75 per barrel. Those contracts were terrific when the price went above $100 per barrel. As prices fell to under $40 per barrel, [the] contracts became a financial burden to Iraq, and payments to oil companies were delayed.” This problem emerged between 2014 and 2015 due to the oil price decline at that time, and later during the price collapse amid the 2020 pandemic.

Iraq holds the fifth largest oil reserves in the world at around 140 billion barrels as shown in Figure (2) below. For various reasons, its production has remained low and has never reflected its full potential. Figure (3) on Iraq’s oil production since 1965 shows that Iraq’s output collapsed several times due to wars, but it started rising steadily from 2011 onwards. The decline in recent years was related to the OPEC+ quota and the COVID pandemic.

Figure (2)

Figure (3)

The Oil Question

Iraq’s crude oil output reached over 4 mb/d in 2015 after various challenges and knowing that there were periods such as in 2008 when crude oil output averaged less than 1.5 mb/d, according to Vogler. This development or success in raising oil output despite instability on multiple levels has been interpreted differently. We all agree that the US invasion was motivated by an oil agenda. The objective, however, was not to secure Iraqi oil for the US as many still believe because this goes against the principles of energy and national security.

Prior to the US invasion, Iraq was under heavy international sanctions imposed following Baghdad’s decision to invade Kuwait in 1990. Sanctions were meant to bring the collapse of the regime of former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein, but this obviously did not happen. The UN established the so-called Oil-for-Food Program which was supposed to allow Iraq to sell oil under the program to pay for humanitarian supplies and ease the devastating impact of sanctions on the civilian population. However, the program was embroiled in corruption which generated hefty profits for the Iraqi government. This could be compared in some parts to the current G7-led price cap imposed on Russian oil exports. Western countries do not want oil prices to rise, and for this reason, they want to ensure the continuous flow of Russian oil but be able to control revenues in one way or the other.

Controlling the oil money was the objective of the 2003 invasion.

When the decision was taken to invade Iraq, the aim was to control the country’s oil reserves and completely cut the flow of oil revenues to Saddam’s regime. So, the strategic goal was to bring about the fall of the regime and use oil revenues to fund the new political system in Iraq and not the money of US taxpayers. Therefore, the role of oil was strategic and extremely important to the goals of the invasion. This explains statements by US officials about the importance of Iraqi oil and the “protection” that the US army offered to some oil facilities and the oil ministry. But this had nothing to do with the US desire to import Iraqi crude oil. The US would have been able to secure Iraqi crude shipments without the war.

Many US officials believed that establishing a new friendly regime, and financing it with Iraq’s own oil revenues, would be successful once a transitional government, the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), was established. This was unrealistic. The outcome was violent, tumultuous, corruption-ridden, and atrocious.

It is true that Iraq’s crude oil output managed to reach 4.4 mb/d by the end of 2015, the energy sector, however, remained and still is plagued with the former regime’s legacies. For instance, the subsidy program in Iraq has been left unchanged since 2003 with all its flaws, and it currently constitutes a dangerous burden on the government’s treasury. Former Iraqi Finance Minister Dr. Ali Allawi says in his book, The Occupation of Iraq: Winning the War, Losing the Peace, that the CPA decided not to alter the subsidy program. “The CPA began to import and distribute petroleum products, which it subsequently allowed to be sold at official giveaway prices. This not only opened the way for unrestricted state imports of oil derivatives, but it also indefinitely postponed the need to reform their price structure,” Dr. Allawi writes in his book. And this is an important point that former Iraqi Electricity Minister Dr. Luay AlKhateeb highlighted on March 21 during a Twitter Space organized by Attaqa, the first energy-focused media platform in Arabic.

Dr. AlKhatteeb noted for instance that the crisis in the refining sector is rooted in the problem of subsidies. “Government subsidies will increase demand to levels beyond control,” he said. “And as we know, when the price is zero, demand is infinite. Therefore, Iraq needs to focus on addressing this, and direct subsidies to groups that need social protection, as well as specific sectors,” he added.

Upstream Vs. Downstream

Throughout the past years, Iraq’s primary goal was to increase crude oil production and today production capacity stands at around 5 mb/d. However, output has been lower due to technical issues on the one hand, and the OPEC+ quota on the other (see Figure 4).

Although Baghdad has an ambitious plan to boost capacity to around 8 mb/d by around 2027, this is unlikely to happen before the required infrastructure is put in place. Iraq urgently needs to rehabilitate its underwater oil pipelines in Basrah, which has been a pressing issue for more than a decade now, increase storage capacity, and implement one of its critical projects and that’s the Common Seawater Supply Project (CSSP) to desalinate seawater that flows into oilfields. For over a decade now Iraq has been expressing it ambitions to boost production. In 2010 Baghdad announced it wanted to raise production capacity to 12 mb/d by 2017. At that time, our own Dr. Anas Alhajji wrote an article published in World Oil magazine in June 2010 about a field-by-field study he conducted with his team and which predicted that the growth, in the base case, will be around 4.9 mb/d. The study was spot on.

Figure (4)

Regarding Iraq’s crude oil exports, destinations have changed after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Figure (5) shows how crude oil exports from Basrah in southern Iraq to Greece, Italy, and Spain have increased, while exports to India have decreased. Iraq’s oil revenues, meanwhile, climbed to a record high in 2022 as shown in Figure (6). The Figure shows Iraq’s monthly oil exports and oil revenues as reported by the Ministry of Oil (MoO) and the State Organization for Marketing of Oil (SOMO).

Figure (5)

Figure (6)

Prioritizing oil production was done at the expense of the downstream sector which was badly damaged during the different wars Iraq experienced including the war against ISIS between 2013 and 2017. Ignoring the development of Iraq’s refining sector has meant that the federal government needs to spend more than $2 billion a year on imported gasoline and gasoil.

“Over the past years, Iraq saw acute shortages in petroleum products and energy in general since it relies on importing more than 50 percent of its needs of petroleum products,” Attaqa quoted Iraqi economist, Alaa al-Fahed, as saying in an interview on March 22.

This financial hemorrhage is still ongoing in the absence of essential reforms which remain ink on white papers. Although last year, Iraq's oil ministry announced the start of trial operations at the 140,000 b/d Karbala refinery, which is considered part of Iraq's refinery upgrade plans to address product imbalance and improve product yields, the country will most likely continue to remain a net importer of gasoline and gasoil up to 2030.

Gas Sector

Iraq’s energy challenges extend to the gas sector too. Although it has the 12th largest gas reserves in the world (see Figure 7), federal Iraq produces only 43% of natural gas for domestic use. According to Iraqi officials in 2021, Iraq was flaring during that year around 45% of its 2.8 billion cubic feet per day (bcf) of gas output as shown in Figure (8). Gas flaring refers to the process of burning associated natural gas instead of capturing and utilizing it. Although Iraq has been in talks with some international companies to capture its gas, there are various obstacles to achieving this, particularly at a time when Iraq is focused on boosting oil production. These companies have included Chinese firms whose presence has been increasing in Iraq over the past years.

The challenges to developing Iraq’s gas sector also include rampant corruption that has been preventing the development of the energy sector. In an interview with Attaqa, Iraqi economist Mustafa Hantoush said Iraq requires billions of dollars in investment to develop its gas sector, but corruption and other factors will likely obstruct development efforts.

“Iraq needs around $70 billion in investment for the gas sector, but the government’s treasury does not have this sum of money. We may resort to new bid rounds, but this requires great effort. Also, widespread corruption affects the public sector’s investments in gas,” Attaqa quoted Hantoush as saying.

Figure (7)

Figure (8)

In the meantime, Iraq is still heavily reliant on gas imports from neighboring Iran. It is supposed to import around 45-70 million cubic meters per day from Iran annually, in addition to electricity imports. In 2021 Baghdad paid about $4 billion for these imports. Gas imports are unstable supplies that can be halted due to technical problems, late payments, or high gas demand inside Iran. Dr. AlKhateeb noted this acute problem on March 21 during the Twitter Space organized by Attaqa, saying: “Iran has its own problems in addressing power demand and gas in winter seasons. When I was the electricity minister [2018-2020], Tehran told us to develop our own resources because the Iranian government needed to address its own domestic demand.”

Power Sector

Turning to the electricity sector, despite billions of dollars in investment since 2003, the infrastructure remains dilapidated, with the government focusing its plans on production without developing the transmission and distribution sectors. These problems have gravely affected Iraq’s economic development. The gap between supply and demand remains between 8000MW-10,000 MW, according to Dr. AlKhateeb. Federal Iraq’s design power capacity is around 37,000 MW. Last summer, the government failed to produce more than 22,250 MW, according to a research paper by Harry Istepanian and Noam Raydan published in 2022 by the Baghdad-based Al Bayan Center, while peak daily power demand was at around 36,000 MW. The one side that usually benefits from this gap between demand and supply is a network of politically connected private generators.

The Future

Iraq says that it wants to boost crude oil production, capture its gas, improve refinery outputs, and provide better electricity services that will contribute to the development of its economy. To achieve all these goals, however, Iraq urgently needs to update important legislations to attract private sector investments in various energy sectors, upgrade its infrastructure, including pipelines and storage, as well as the transmission and distribution sectors, and not only focus on production in both the oil and power sectors. And most importantly, Iraq needs to show seriousness in combatting corruption that is preventing the development of its energy sector. Recently announced projects such as TotalEnergies’ $27 billion contract with Iraq that covers oil, natural gas, and renewables, will not be successful without all these reforms we have mentioned.

On oil production and transportation specifically, expanding output to 8 mb/d will generate new challenges, particularly since Iraq has limited ports. It exports its Basrah crude through the Gulf region, while crude from northern oilfields is exported via Turkey’s Ceyhan port (very small amounts are also trucked to Jordan). The multi-billion dollar Basra-Aqaba oil pipeline, and which is an old idea that dates to at least 1980s, and if implemented, will be able to carry only around 1 mb/d through the section stretching from Haditha in western Iraq to the Red Sea port of Aqaba in Jordan. In 2013, Iraq and Jordan signed a framework agreement for the pipeline, but political, security, and economic factors have delayed the project and forced changes to the original blueprint on many occasions.

Another problematic issue is how to increase oil and gas production significantly in a world that is seeking to fight climate change. Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions have more than doubled in Iraq since the US invasion, reaching around 145 million tons in 2022. Furthermore, the expansion of Iraq’s oil production capacity implies that shared fields with Iran have to be settled, and this is going to be a very contentious issue.

Solving Iraq’s energy problems will take time. Our own long-term outlook shows that the world needs an increase in Iraq’s oil production to above 7 mb/d as global oil demand is expected to continue to grow despite the high penetration of electric vehicles. In other words, there is an economic justification for the increase in Iraq’s production capacity and this increase in capacity will have no negative impact on oil prices. Instead, it will contribute to the stability of the market.

Figure (9) shows Iraq’s oil production and oil prices over the past decades and up to 2017 when output increased and stabilized. The chart also shows the impact of Iraqi oil production on oil prices, especially during turbulent periods like the Iraq-Iran war, the invasion of Kuwait, and the Gulf war that followed the UN Oil-for-Food Program, and the US invasion of Iraq and its aftermath. Most importantly, it shows that the act of significantly increasing production takes time, at least three years.

Figure (9)

Additionally, future increases in Iraq’s oil production are not expected to cause problems for OPEC+ unless demand declines, especially in the event of a recession.

Finally, some may ask: if Iraq increased its output to 8 mb/d in the next few years, and Saudi Aramco produced at maximum capacity by then, will Iraq become the swing producer, or will it produce at maximum? While this is an academic question at this time, it will have a tremendous impact on the markets during periods of low economic growth and recessions as Iraq may not lower production enough to help balance the market.