EOA 2023 Oil Market Outlook

One of the least appreciated risks in the oil market: The increased substitution among energy sources

MAIN TAKEAWAYS

2023 is expected to be a tale of two opposite halves: bearish to neutral in the first half and bullish in the second.

Global oil demand is expected to reach a record high in 2023, defying all earlier forecasts of peak demand in 2019.

Almost all average price forecasts for 2023 are between $80/b and $100/b. Our estimate is toward the lower end of these forecasts.

Any OPEC+ production cuts will create a price floor but may not raise prices significantly.

Refilling the US SPR will have a limited impact on the oil market.

Russia’s oil exports are not expected to decline significantly in 2023, but the Russian government may be forced to reduce taxes on oil companies.

The impact of China’s reopening on energy markets will be felt in the second half of 2023. Beijing, however, will likely release oil from its SPR as oil demand and prices rise.

The return to fossil fuels in Europe and some US regions last year to address energy needs was unprecedented. A repeat in 2023 should call for a new way of thinking with a focus on relative prices of energy sources.

SUMMARY

2022 was a historic year for all energy markets as we noted in last week's newsletter. In the oil market specifically, last year saw the largest release of oil from the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) in history, as well as unprecedented western sanctions against a top oil producer like Russia, while China, the world’s largest oil importer, experienced prolonged COVID lockdowns. In Europe, some countries which adhered over the past decades to anti-fuel subsidies policies found themselves compelled to change course amid a biting energy crisis that took a heavy toll on European consumers. The energy crisis also forced some countries in Europe and regions in the US to return to oil-fired power generation and heating. All these momentous events changed the direction of global oil trade.

As for 2023, we don’t expect it to be as historic as last year.

In today’s newsletter, we share with our readers the EOA’s 2023 oil market outlook, in addition to other forecasts that have been made by different groups. Based on the data we have compiled, it is most likely that the first half of this year will be different from the second. Our initial assessments show that during the first half of 2023, the oil market will be in a bearish or neutral state, while bullish in the second half, especially in the fourth quarter. Other publications have arrived at similar assessments, but the difference between our forecasts and what’s been published is the duration of the state of bearishness or bullishness.

Regarding global oil demand, we expect it to grow and hit a record high in 2023, even in the event of an economic recession during the first half of the year. Our forecast differs from others in the rate of growth. Our estimated growth is more conservative than most due to the wobbly economies of China and Europe. The recent decline in crude oil prices, amid Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine, and relatively high global inflation, will most likely prevent higher oil demand growth in oil-producing countries. Meanwhile, refining issues will lead to higher petroleum products prices relative to crude prices, especially with respect to diesel prices, which could be higher than what’s recorded in normal circumstances.

Regarding the issue of refilling the US SPR, and if it occurs in 2023, we believe that it will have a limited impact on oil demand and prices, and we will revisit this topic in detail in the next few weeks. We also believe that China’s reopening will have a limited impact on global oil demand in the first half of 2023, thus leaving the market between a bearish and neutral state. However, we believe that this state will then turn bullish in the second half.

Meanwhile, growth in global oil production in 2023 will mostly come from non-OPEC members. As for Russian crude oil production, it is expected to contract, but not at significant rates. As we noted in our previous newsletters, the impact of western sanctions and the G7-led price cap on Russian oil will be limited as Moscow will continue to divert its oil from Europe to other regions, either directly or through various shipping schemes. We also believe that Russian oil will end up in Europe despite sanctions.

While lower investments will hamper Russian production, most of this impact on Russia’s oil industry will be seen in 2024 and 2025. In the meantime, lower oil prices accompanied by large discounts on sold Russian oil will have a significant impact on Moscow’s finances. Under such circumstances, the Russian government will have to further reduce taxes to keep oil exports flowing at high rates, otherwise, companies will start shutting in oil production.

Moving to Libya and Nigeria, if the security environment continued to improve in these two OPEC members, this could increase their oil production, thus leading to a significant rise in OPEC’s oil output that could exceed the 2022 levels. As for oil output policies, we don’t expect surprising decisions from OPEC/OPEC+ in 2023.

Turning to oil production in the US, we expect growth, including in shale production. However, low natural gas prices, and sometimes negative prices, could threaten oil production in certain tight oil plays. Offshore activities, meanwhile, are expected to increase, including in the Gulf of Mexico.

With respect to oil inventories, we expect a build in crude oil inventories in the first half and a draw in the second. A recession (or partial recession for those who insist on the official definition of a recession which is a decline in output for six months in a row) would make the second half less bullish because of the additional inventory build. As a result, oil prices are expected to be weak in the first quarter and continue to improve as we move toward the end of 2023. Absent any major political events, oil prices could hit $100/barrel and even breach that in the fourth quarter of 2023.

Global Oil Demand in 2023

Global oil demand, which includes petroleum products, Natural Gas Liquids (NGLs), refinery gains, and biofuels, will continue to grow in 2023, even in the event of a recession, but at a slower pace than most forecasts. In China, the world’s second-biggest oil consumer, most of the rebound in oil demand in the first half of 2023 will be triggered by the transportation sector, and it will take until the fourth quarter to see the rest of China’s economy recovering. Europe, meanwhile, will experience lackluster economic growth, and we expect a negative year-over-year (YOY) demand growth. The demand growth of oil-producing countries will be affected due to increased import costs, especially food supplies, and declining oil prices. Oil demand growth is now already lower than earlier expectations.

In the US, fears of an economic recession and lower economic growth, accompanied by relatively higher petroleum products prices, will also limit growth in oil demand. Further restrictions are also expected as most developing countries are experiencing depreciating national currencies amid budgetary deficits.

Overview of Forecasts

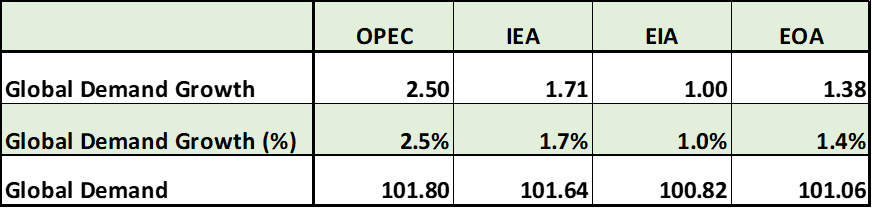

In Table (1) below we list our global oil demand forecast versus those of OPEC, the International Energy Agency (IEA), and the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), assuming no recession takes place this year. Our 2023 demand growth forecast stands at an average of 1.38 million barrels per day (about 1.4%), which is lower than that of OPEC and the IEA, but higher than the EIA’s forecast. Forecasts by major banks and consulting houses are not far different from what is shown in the table below.

Table (1)

Global Oil Demand Forecasts: A Comparison (mb/d) *

Source: EIA, 2022, EOA, 2023, IEA, 2022. And OPEC, 2022. * Includes biofuel

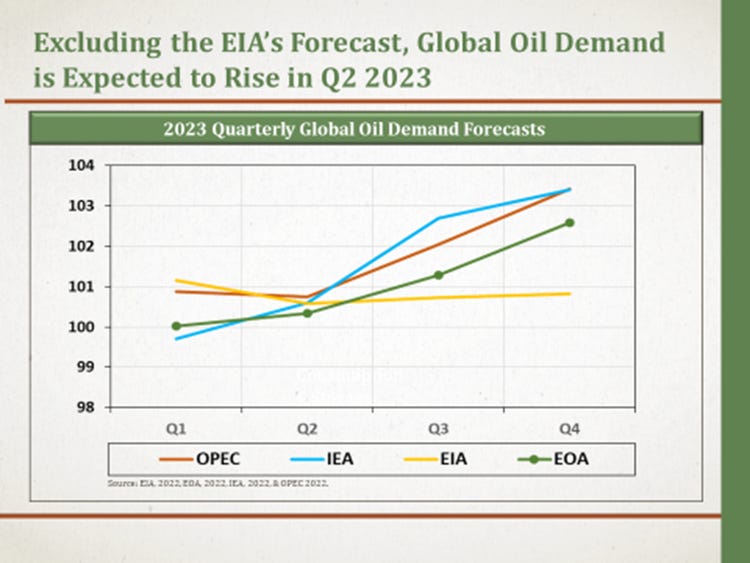

Figure (1) below compares various forecasts on a quarterly basis. The chart mainly focuses on the trends, and we advise against comparing yearly levels given that definitions of oil and liquids differ from one organization to another, and due to the divergent oil demand estimates over the past years. The key takeaway from the chart is that we, as the EOA, expect high demand growth in the second half of 2023 similar to the OPEC and IEA’s forecasts.

Figure (1)

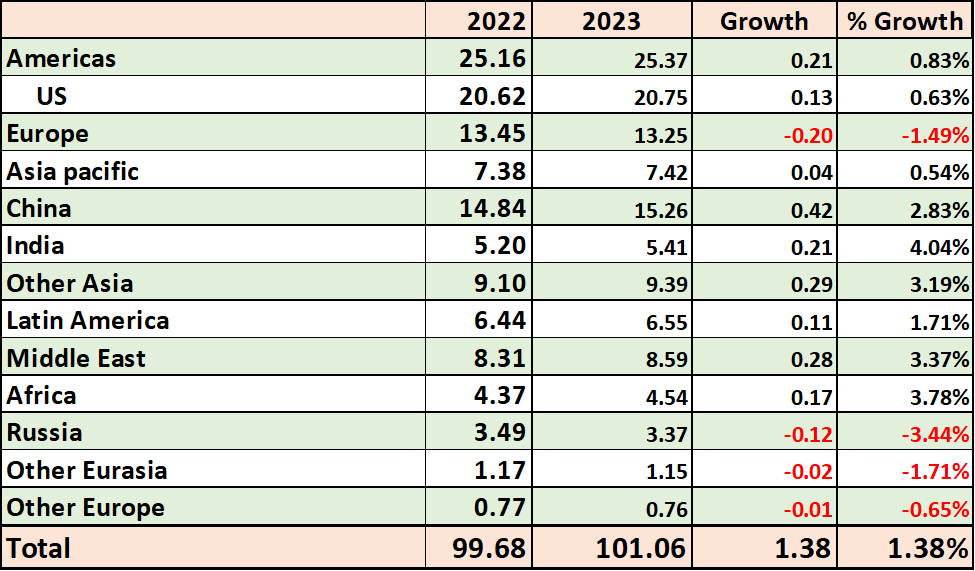

In Table (2) below, we list our global oil demand forecasts by region. We expect a decline in oil demand in Europe, Russia, and other areas, mainly because of worsening economic conditions. Europe’s oil demand is expected to decline by about 200,000 b/d, while Russia’s oil demand is expected to drop by around 120,000 b/d.

Table (2)

Global Oil Demand by Region/Country

Source: EOA, 2023

Global Oil Demand in a Recession Scenario

Forecasting global oil demand becomes complicated in a recession scenario. Through applying game theory, we came up with several scenarios, but we will cut to the chase and share with readers our forecast below.

Global oil demand would grow in the event of a mild recession by an average of 820,000 b/d in 2023 relative to the 2022 average. While in the case of a severe recession, demand would drop by about 380,000 b/d. This small decline, however, should not be interpreted as insignificant because it means that a severe recession would wipe out all the demand growth. In other words, a severe recession would lower global oil demand by up to 1.8 mb/d— the expected growth without a recession in addition to the decline year-over-year.

For our forecast in a recession scenario, we took various factors into consideration, including the extent of the recession, the reactions of various groups, including OPEC/OPEC+, banks, investors, and private firms, as well as the impact of a global recession on Russia.

We also downplayed the possibility of political turmoil in any of the oil-producing countries in a recession scenario. History shows that most political turbulences that took place in oil-producing countries in the past occurred during periods of high oil prices and rarely happened during a state of low oil prices.

Global Oil Supply in 2023

Before sharing our expectations for oil production in 2023, we would like to remind our readers of four fundamental concepts we published in last week’s newsletter, and which are important for a better understanding of the supply side of the oil market:

There is a difference between “production” and “supply”. Oil in the SPR is oil produced in past years. Releasing oil from the SPR is an increase in supply. A reduction in commercial oil inventories to meet demand implies supplies are higher than production.

There is a difference between “actual OPEC production” and the “Call on OPEC”. The first is actual production, while the second is what OPEC should produce to fill the gap between global oil demand and non-OPEC production. Actual production could be higher, lower, or equal to the Call on OPEC.

There is a difference between the OPEC+ production ceiling (quota or production target) and actual production. OPEC+ production decisions focus on the production ceiling, not actual production. A case in point is when OPEC+ decided in early October 2022 to cut production by 2 mb/d—this was from the production ceiling. The actual production cut was way lower since many countries could not meet their quotas in 2022.

Demand numbers include all liquids: crude, condensate, NGLs, refinery gains, and biofuels. Most production numbers focus on crude and lease condensates. One of the emerging problems now is that crude oil production numbers include NGLs.

Overview of Supply Forecasts

Non-OPEC liquids supply is expected to increase, and it will mostly originate from the US, Norway, Brazil, Canada, Kazakhstan, and Guyana. The Call on OPEC is also expected to increase, but the OPEC actual production may be different from the Call on OPEC, leading to changes in inventories.

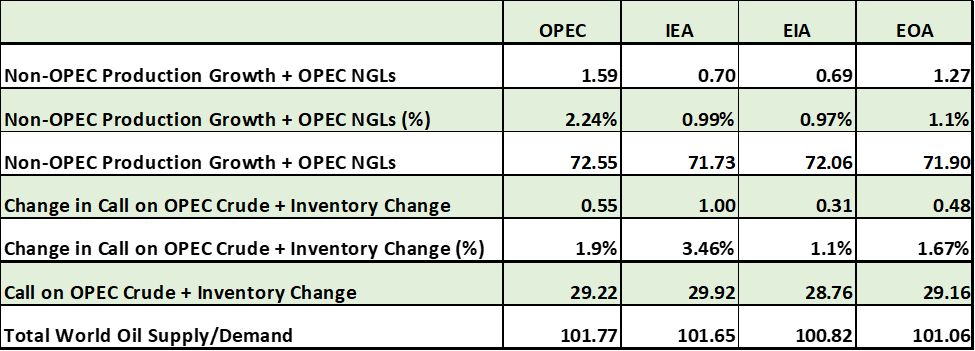

Table (3) below shows the various liquids supply forecasts for 2023. The first row indicates growth in non-OPEC supply using data from different organizations, in addition to our own forecast as the EOA. The growth ranges from the low of 690,000 b/d estimated by the EIA to the high of 1.59 mb/d forecasted by OPEC. In our turn, we expect non-OPEC supply to grow by 1.27 mb/d. The high number estimated by OPEC shows that the group is not taking any chances and is assuming the worst scenario: a major increase in non-OPEC supply. The low numbers of the EIA and IEA also signal that the two are not taking any chances and want to show that OPEC+ needs to increase production to avoid a large inventory draw.

While the fourth row is intended to show the “Call on OPEC”, such numbers need to be interpreted carefully. For example, the IEA expects the difference between total world demand and non-OPEC production to stand at around 1 mb/d. So, how will this gap be filled? There are three possibilities:

The total gap will be filled by OPEC. OPEC production in this case would increase by 1 mb/d (this is actual production, not ceiling or quota).

If OPEC is not able to increase production by the whole amount, then the rest of the gap will be filled by withdrawals from commercial inventories, and probably SPRs. For example, if OPEC increases production by only 700,000 b/d, then the draw from inventories and SPRs would be 300,000 b/d.

If the gap is larger than the increase in OPEC production and the draw from inventories, prices will rise high enough to reduce demand. For example, the IEA would end up lowering its demand estimates from the stated 101.64 mb/d.

But what if non-OPEC producers failed to deliver the estimated production? In this case, the gap between world demand and non-OPEC production will grow larger, and the demand for OPEC’s oil will increase. In the case OPEC also couldn’t deliver the required amount, there will be withdrawals from inventories. If the difference is large and prices rise significantly, governments of top oil-consuming countries may return to withdrawals from their SPRs.

Our view is that the amount that could be released from both the “Call on OPEC” (what OPEC should produce to fill the gap between global oil demand and non-OPEC production) and inventories will be small: 480,000 b/d. We believe that OPEC will produce above the Call on OPEC (whatever that level is, since these numbers change frequently). This will allow for inventory build, mostly in the first half of the year. In short, there is enough spare capacity in some OPEC countries that can cover any demand increase in 2023, but it will be thin in the fourth quarter.

Table (3)

2023 Non-OPEC Production and Call on OPEC

Source: EIA, 2022, EOA, 2023, IEA, 2022. And OPEC, 2022.

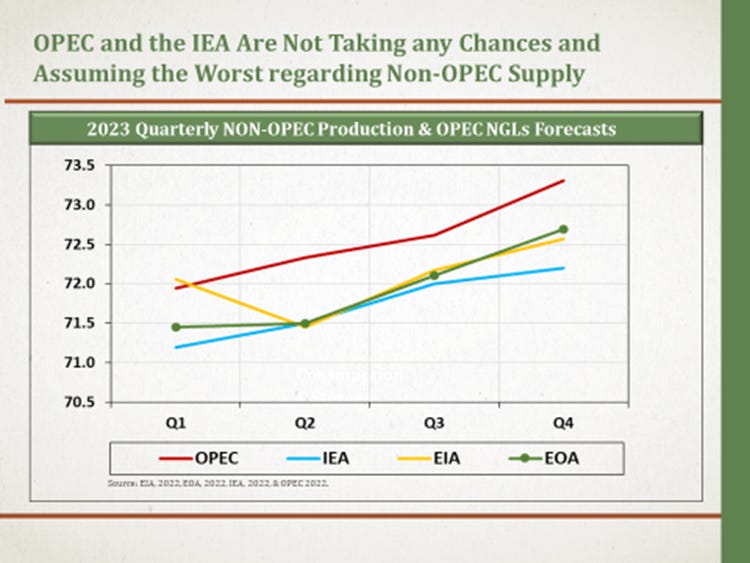

Figures (2) and (3) sum up the forecasts for non-OPEC production and the Call on OPEC on a quarterly basis. They all show that production would respond to higher demand in the second half of 2023.

Figure (2)

Figure (3)

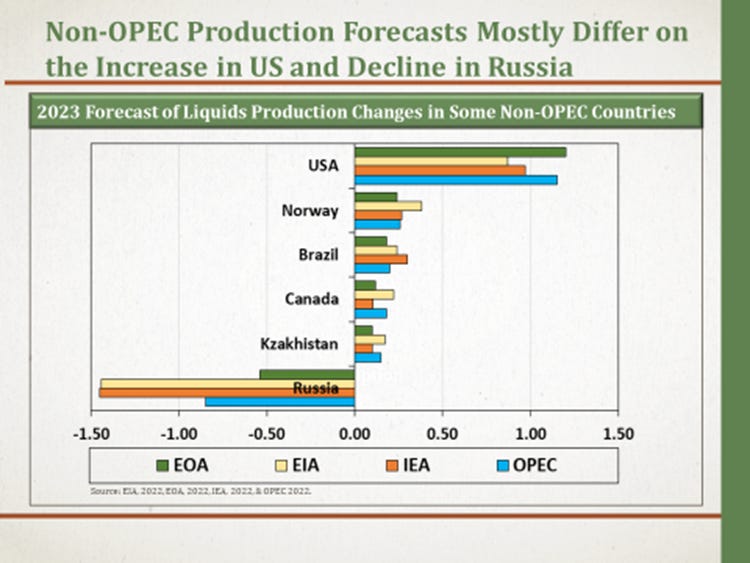

Figure (4) below shows the origins of most production increases based on different forecasts. Our forecasts differ from others in two major ways: First, regarding US oil additions, our forecast is higher than others. Second, and with respect to the decline in Russian oil production, our forecast is way lower than other predictions. It is also worth noting that OPEC’s estimate of the drop in Russian oil output also includes production cuts agreed on by OPEC+ members last October.

Figure (4)

Oil Prices in 2023

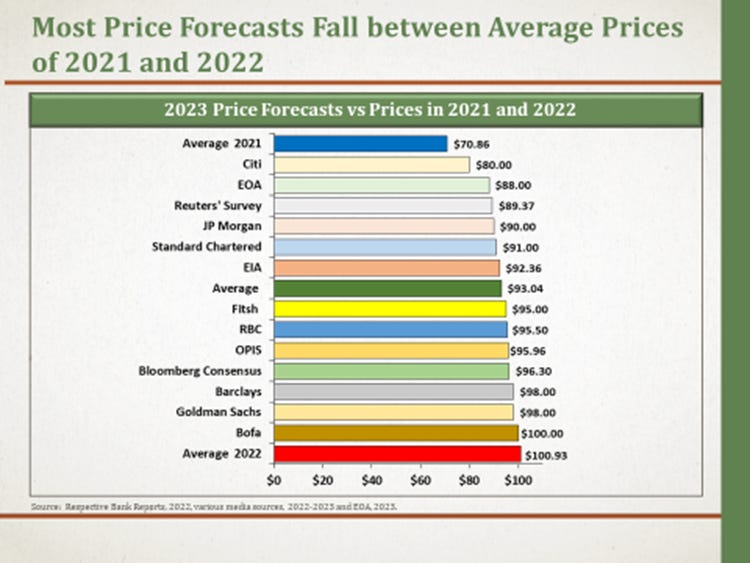

Two points stand out when looking at various price forecasts for Brent crude oil:

Most forecasts for the average Brent price in 2023 fall between the average prices of 2021 and 2022.

Some groups have “predicted prices in 2023 to be between $80/b and $100/b”. This forecast, however, is of no real value because it covers every forecast shown in Figure (5) below.

Based on our above-mentioned views on oil supply and demand, along with the issues discussed in the following section, we estimate Brent prices to average $88/b in 2023, which is next to the lowest in the list of forecasts in Figure (5).

The oil market is expected to remain weak in the first half of 2023, mainly in the first quarter. While we are bullish on the second half, especially in the second quarter of it, low prices in the first half will weigh on the average price for the whole year. In case of a recession in the first half, or even a decline in outputs for 3-4 months, oil prices will decline further. OPEC’s reaction is expected to be supportive, but not enough to raise prices to $100/b as we discuss below.

Figure (5)

Major Issues and Concerns to Watch in 2023

We discuss below four key issues related to OPEC/OPEC+ measures, Russian oil production and exports, refilling the US SPR, and others that could challenge our forecasts.

1- Will OPEC/OPEC+ Meet Soon for Additional Output Cuts?

The OPEC ministerial meeting is not expected to take place before June 4, 2023. However, during their meeting on December 4, 2022, OPEC+ ministers adjusted “the frequency of the monthly meetings to become every two months for the Joint Ministerial Monitoring Committee (JMMC) and the authority of the JMMC to hold additional meetings, or to request an OPEC and non-OPEC Ministerial Meeting at any time to address market developments if necessary.”

If oil prices continue to decline, OPEC+ has two choices: either the JMMC calls for an emergency meeting or waits for the JMMC recommendation in February.

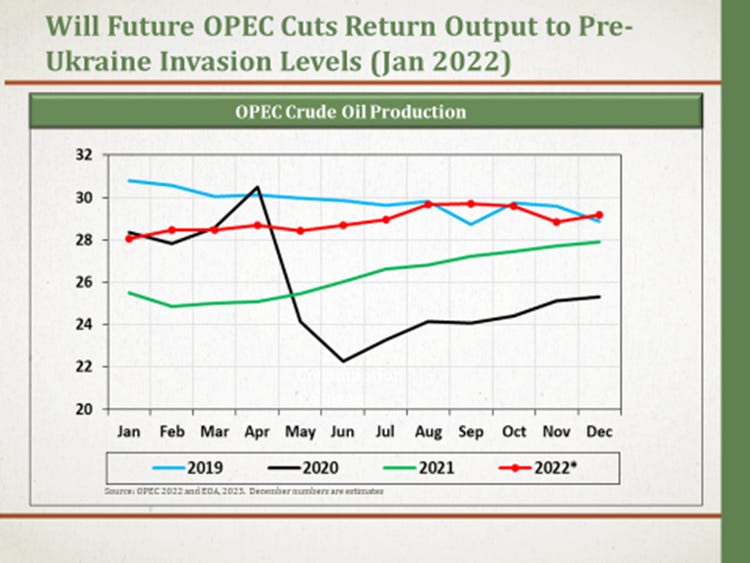

If the JMMC calls for a full ministerial meeting, this could signal that OPEC+ ministers will most likely convene to agree on a production cut. We believe that any cut will NOT be aggressive, and its role will most likely be directed at preventing a large build in global oil inventories and indirectly maintaining Brent crude oil prices above $75/b. Any cut will return oil production to levels last seen before Russia invaded Ukraine (see Figure 6 below).

It is also worth noting that a production cut isn’t necessarily made to increase oil prices. Preventing oil prices from declining further is a successful action on its own.

In case of a recession, global or regional, we predict that OPEC/OPEC+ will agree on a large production cut. We also believe that OPEC/OPEC+ will defend a price floor of $60/b (Brent).

Figure (6)

2- Will Russian Oil Production and Exports Decline Significantly in 2023?

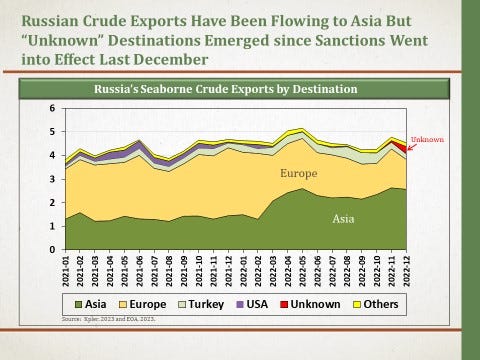

In our previous newsletters, we covered Western sanctions and the G7-led price cap on Russian oil, noting that the impact of these restrictions will be limited. We said that Russian oil companies could divert part of their oil shipments, which used to be exported to Europe, to other countries as shown in Figure (7) below. But some Russian crude will still reach Europe through different means. Based on our calculations, we believe that Russian companies will have a serious problem selling between 300,000 b/d and 400,000 b/d. This conclusion is supported by the fact that some shipments have unknown destinations, as shown in the red area in the chart below.

While Western sanctions will NOT sharply reduce Russian oil production and exports (in fact the price cap legalized all Russian exports since they are sold below the $60 price cap), lower oil prices will be troubling for Russian oil companies and the government’s budget. Recent reports indicated that Russia’s flagship Urals crude oil was sold in the high $30s. The breakeven is about $55/b, and about half of this cost is government taxes. If the Russian government wants companies to continue exporting at such low prices, it will have to reduce taxes. Lower taxes, however, mean a large budget deficit at a time when Russia is cut off from most of the global financial system.

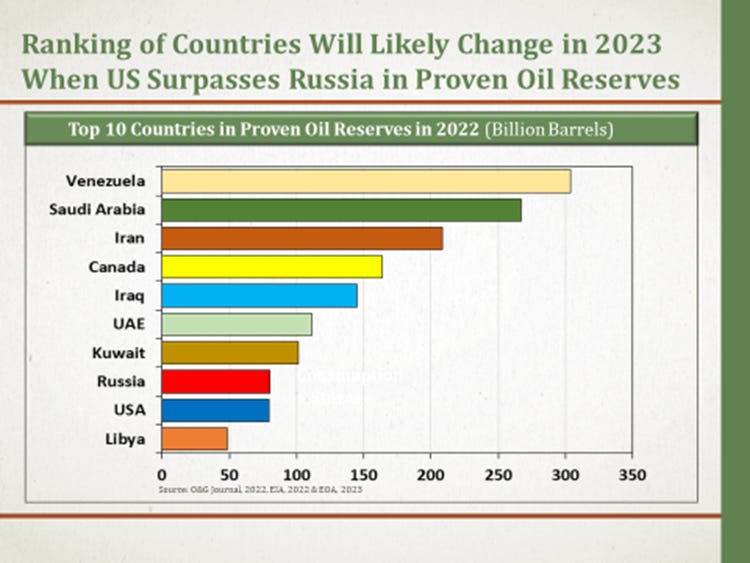

As Russia’s war in Ukraine protracts, and sanctions on Moscow deepen, lower investment and a lack of spare parts will heavily affect Russian oil production, particularly after 2023. From now until the end of the year, we expect Russian oil production to decline by about 600,000 b/d which includes the 300,000 b/d-400,000 b/d mentioned above. A decline in investments would reduce Russia’s proven oil reserves, thus allowing the US to surpass Russia as the 8th largest holder of proven oil reserves in the world. (See Figure 8 below).

Figure (7)

Figure (8)

3- What is the Impact of Refilling the US SPR?

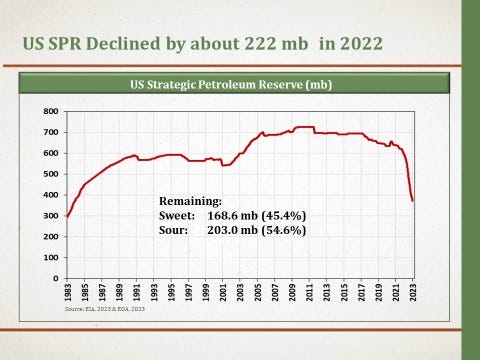

As we anticipated in our newsletter on December 18, 2022, the US administration has decided to walk away from a plan to refill the SPR with three million barrels of sour crude oil in February. The administration released about 221 mb of crude from the SPR in 2022, which included the 180 mb US President Joe Biden authorized in March 2022 (see Figure 9 below).

In our view, if the US administration decides to refill the SPR later this year, the following will likely happen:

Any refill will be partial and will be around 60-90 mb, if any.

Most of the purchased amount will be medium sour crude oil, and shale producers will not benefit from this since they produce light sweet crude.

Prices for medium sour crude will be around $40 or lower.

The only way oil prices for medium sour crude oil could decline to such levels in 2023 is if we end up with a severe recession. The Administration may find a short window to purchase oil before OPEC/OPEC+ announce a cut production. In other words, the ability of the Biden administration to refill the SPR at the desired prices is in the hands of Saudi Arabia (this may be a hard truth for those who do not like to hear it).

The impact of an SPR refill, and if it happens, will be very limited. In addition to having an amount that is relatively small, buying during a period of negative sentiment creates a price floor or reduces the decline. Unlike what the US Department of Energy (DOE) has said, buying 60-90 mb of oil will not change the upstream investment decision of any oil company. Purchasing 60 mb-90 mb over a period of a few months will have no impact on offshore projects that are designed to operate for 20 years or more. In addition, most of the purchased oil may be imported or may come from the Gulf of Mexico if the US government insists on buying domestic oil.

Figure (9)

4- What Could Go Wrong with Our Forecasts?

Several factors can challenge forecasts, including changing political circumstances in oil-producing countries like Russia, Iran, and Venezuela, and natural events such as hurricanes that usually hit the US Gulf Coast. Any events that lead to changes in supply or demand would render our forecasts inaccurate. In what follows, we focus on some of these issues that have been overlooked by others, and which could invalidate our forecasts for this year.

The first issue is related to the relationship between oil, natural gas, and LNG. For example, hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico could lead to a halt in US LNG exports to Europe. In this case, LNG prices would increase substantially, forcing power companies, factories, and consumers to switch to oil products, therefore leading to a rise in oil demand to levels above existing forecasts.

A halt in LNG exports, meanwhile, will lead to lower natural gas prices in the US. Also, low and negative natural gas prices in some hubs in the US may force some oil producers to reduce production, resulting in oil production levels being lower than expected.

The second issue is regarding possible massive and extended power outages due to weather conditions or other factors. Private power generation, which uses petroleum products, increases in such circumstances, and this in its turn could raise oil demand to levels above existing forecasts. Historical evidence shows that an increase in oil demand under such conditions can reach 800,000 b/d.

The third issue is related to the possibility of a severe summer heat wave in the Middle East and North Africa that could lead to a sharp rise in demand for space cooling. Power plants in these regions usually meet this increase in demand by using fuel oil and diesel, and in some cases crude oil. In this case, there won’t only be an increase in demand, but such an increase could come at the expense of oil exports, therefore reducing global supplies while oil production is increasing. Historically, such developments have always been bullish, and for this reason, there is a possibility that the third quarter of 2023, in particular, will be bullish more than what has been expected in this outlook.

The fourth and final issue is related to US shale production growth, and crude oil quality. If most, or all the growth comes from sweet crude production and condensates, while Iran, Libya, and Nigeria increase their oil output of this same quality, the oil market will then face a surplus in this type of crude oil. Although this will depend on how refineries will react, such surplus will affect price differentials, which in turn will lead to a change in oil market balances in a way different from what has been forecasted.

In conclusion, 2023 may end up being an uneventful year for the oil market, unlike 2022 which saw unprecedented developments. However, 2023 will be the year when oil demand increases to record-breaking levels. We are also keeping an eye on the US and China: last year, we saw the US reducing its SPR while China was building it, but could 2023 be the year when China releases oil from its SPR while the US focuses on increasing its own reserves?

would like a refound for my 7 day free trial, canceled by still got charged!!!